Moosa Mohammadi

Positions and Education

Education:

1988 M.S. University of Zurich, Switzerland

1993 Ph.D. University of Zurich (Biochemistry), Switzerland

Postdoctoral Training: New York University School of Medicine (Structural Biology)

Academic Appointments:

1997-2001 Assistant Professor of Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine

2001-2007 Associate professor of Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine (tenured as of Sep. 2005)

2007-2021 Professor of Biochemistry & Molecular Pharmacology, New York University School of Medicine

Publications

Web of Science Researcher ID: https://publons.com/researcher/ABA-6745-2020/

H-Index 71 (Web of Science)

Patents

https://patents.justia.com/inventor/moosa-mohammadi

Selected International Talks

2019 – 3rd Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development and Repair Fusion conference, Nassau, Bahamas

2018 – 5th International Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors, Wenzhou, China, Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

2018 – Gordon Research Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development & Disease, Ventura, CA, USA

2016 – 4th International Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors, Wenzhou, China, Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

2016 – Gordon Research Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development & Disease, Honk Kong, China

2014 – Gordon Research Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development & Disease, Ventura, CA, USA

2012 – Gordon Research Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development & Disease, Les Diablerets, Switzerland

2011 – Cell Signaling Networks 2011, 13th IUBMB Conference, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico

2010 – Gordon Research Conference on Fibroblast Growth Factors in Development & Disease: Chair, Ventura, CA, USA

My Research

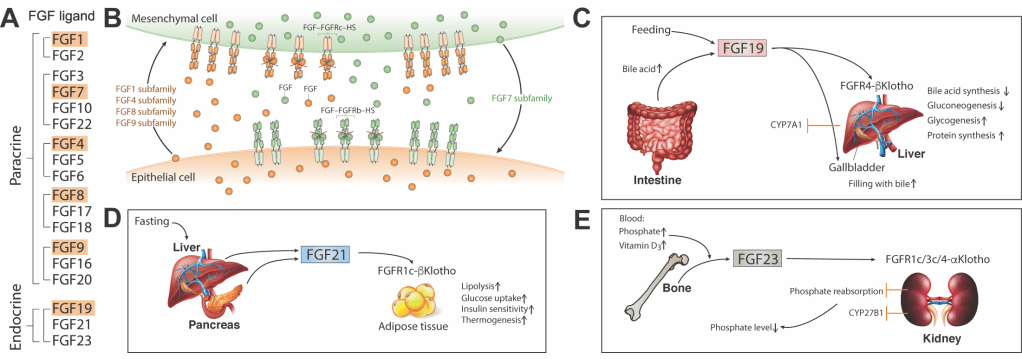

My research is centered on the molecular mechanisms of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling. The human FGF family comprises 18 secreted polypeptides which are grouped into 6 subfamilies based on sequence homology, phylogeny and synteny, and named after their founding members: FGF1, FGF4, FGF7, FGF8, FGF9 and FGF19 (Fig. 1A). Members of the first five subfamilies are hardcore paracrine-acting ligands that mediate a bidirectional signaling loop between epithelium and mesenchyme within organs (Fig. 1B), thereby directing key events throughout embryogenesis including implantation, gastrulation, mesoderm induction, body axis formation, somitogenesis, organogenesis, tissue morphogenesis, patterning, and tissue homeostasis throughout adulthood. Members of the FGF19 subfamily – namely FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23 – are bona fide hormones which mediate gut-liver (Fig. 1C), liver-fat (Fig. 1D) and bone-kidney (Fig. 1E) metabolic axes, respectively, thereby regulating bile acid, lipid, glucose, vitamin D and mineral ion homeostasis. FGFs transduce their pleiotropic effects by binding, dimerizing and thereby activating cell surface cognate FGF receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinases (RTKs; FGFR1-4) in concert with heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans (in the case of paracrine FGFs) and aKlotho and bKlotho co-receptors (in the case of endocrine FGFs); a and bKlotho belong to a novel class of aging and tumor suppressor proteins.

Figure 1. FGF actions in tissue homeostasis and metabolism. (A) 18 mammalian FGF ligands grouped by subfamily and mode of action. Founding members of each subfamily are highlighted. (B) Paracrine FGF-FGFR signaling mediates a bidirectional signaling loop between epithelium and mesenchyme within organs. (C-E) Endocrine FGFs mediate three major hormonal axes:gut-liver (FGF19, C), liver-adipose, (FGF21, D) andbone-kidney (FGF23, E).

Defects in FGF signaling lead to a diverse array of diseases including craniosynostosis and dwarfism syndromes, renal phosphate wasting disorders, aging, tissue degeneration and cancer. Accordingly, FGF signaling has taken center stage for drug discovery for multiple human diseases. Indeed, the efficacy of at least three paracrine FGFs — FGF18 (sprifermin), FGF7 (palifermin) and FGF2 (trafermin) — that are involved in tissue protection, repair, engineering and regeneration are currently under clinical evaluation. Likewise, FGF hormones are promising targets for the treatment of a spectrum of metabolic diseases including type II diabetes, obesity, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), primary biliary cirrhosis, bile acid diarrhea, renal phosphate wasting disorders, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Two small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Erdafitinib (Balversa) and Pemigatinib (Pemazyre), have recently received accelerated FDA approval for the treatment of adult bladder cancer patients harboring gain-of-function mutations in FGFR3 (Balversa), and for adults with non-resectable locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma involving FGFR2 fusion proteins (Pemazyre).

B. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE FIELD The biomedical significance of FGF signaling has been the principal driver of structural studies of this system which I have been undertaking since starting my independent laboratory in 1997. Using a multidisciplinary approach encompassing X-ray crystallography, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) spectroscopy, Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS), and enzymatic and cell-based assays, I have provided key mechanistic insights into the pleiotropic roles played by FGF signaling in human development, metabolism, and disease. My lab has delivered a substantial body of structural data on FGF signaling; accordingly, I have acquired recognition as the leading authority in the structural biology of FGF signaling. As a result, the FGF-FGFR signaling system is one of the structurally best understood systems within the RTK superfamily. I have established numerous fruitful collaborations with developmental biologists, endocrinologists, clinicians, and cell and cancer biologists in the FGF field so as to identify and tackle key biological problems in FGF signaling. Importantly, I have harnessed our current structural insights towards the design and engineering of novel biologics as potential treatments for renal phosphate wasting disorders, chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. In this regard, my laboratory’s research activities have resulted in 11 patent applications to date. Some of my major contributions include:

1. Structural Basis for HS Requirement in Paracrine FGF Signaling The discovery of a requirement for HS proteoglycans in paracrine FGF signaling led to the proposition of numerous models to explain the mechanism by which HS promotes FGF signaling. We showed that HS induces the formation of a 2:2:2 paracrine FGF-FGFR-HS quaternary complex, thereby positioning the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains such that they can be transphosphorylated and consequently activated. This model has unified a wealth of published literature and has had a profound and sustained impact on the FGF signaling field.

2. Molecular Basis for a Co-receptor Role for Klotho Proteins in Endocrine FGF Signaling We showed that the conformations of the HS binding sites in FGF19 subfamily members completely diverge from that of classical paracrine-acting FGFs, with a dramatic reduction in the affinity of these ligands for HS. Consequently, these hormone-like FGFs are able to freely permeate the HS-laden pericellular matrix, enter the blood circulation, and act in an endocrine fashion. To offset their weak HS and FGFR binding affinities, these hormone-like FGFs rely on α- and b-Klotho co-receptors to bind, dimerize and activate their cognate FGFRs in their target tissues. More recently, by solving the crystal structure of a 1:1:1 ternary complex consisting of the naturally shed extracellular domain of α-klotho, the FGFR1c ligand-binding domain, and FGF23 (Fig. 2), we showed that Klotho co-receptors serve as non-enzymatic molecular scaffolds that simultaneously tether endocrine FGF and its cognate FGFR. In doing so, Klotho co-receptors enforce endocrine FGF-FGFR proximity and augment affinity/stability.

Figure 2. Cartoon (left) and surface representation (right) of the FGF23–FGFR1cecto–α-klothoecto ternary complex structure. The α-klotho KL1 (cyan) and KL2 (blue) domains are joined by a short proline-rich linker (yellow; not visible in the surface presentation). FGF23 is in orange with its proteolytic cleavage motif in grey. FGFR1c is in green. CT, C terminus; NT, N terminus.

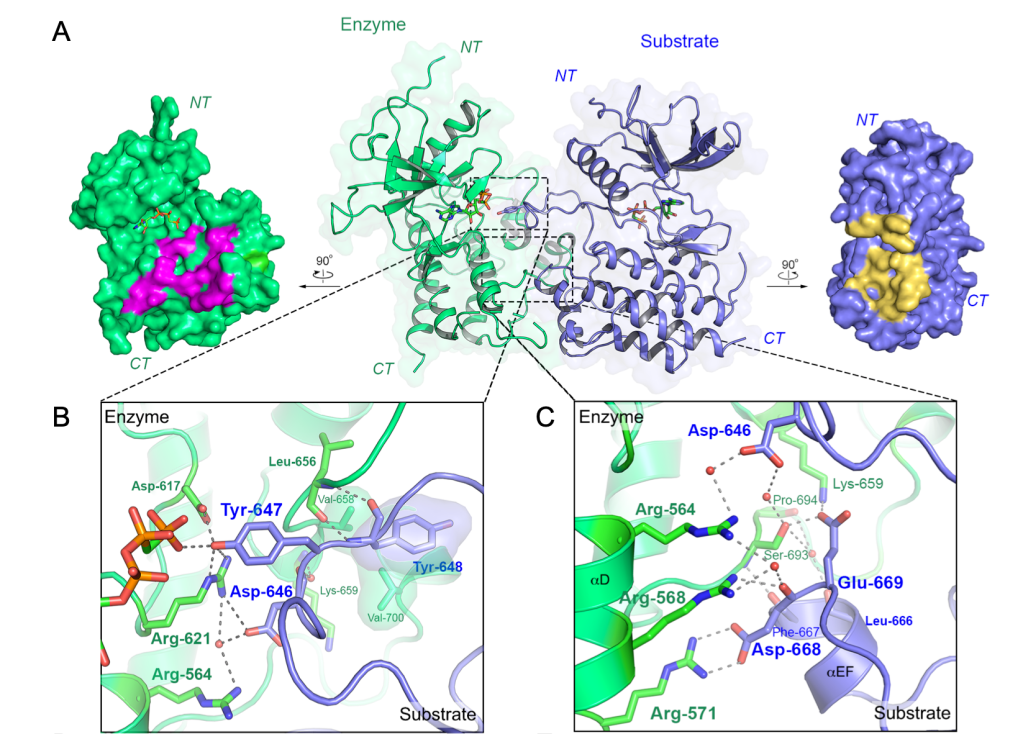

3. Structural Basis for FGFR Kinase A-loop Tyrosine Trans-Autophosphorylation We reported crystallographic snapshots of FGFR kinases embracing each other so as to conduct transphosphorylation on tyrosine residues within either the kinase C-terminal tail, the kinase insert region, or the activation (A)-loop. We found that the latter transphosphorylation reaction, required by almost all RTKs, is mediated by an asymmetric complex that is thermodynamically disadvantaged because of an electrostatic repulsion between enzyme and substrate kinases (Fig. 3). Under physiological conditions, the energetic gain resulting from ligand-induced extracellular domain dimerization overcomes this opposing clash, stabilizing the A-loop transphosphorylating dimer. A pathogenic FGFR gain-of-function mutation promotes formation of the A-loop tyrosine phosphorylation complex by eliminating this repulsive force.

Figure 3. Crystallographic snapshot of an A-loop-transphosphorylating asymmetric complex of FGFR3 kinases. a, Center, overall view of the crystal structure of the FGFR3KR669E asymmetric complex shown as a cartoon superimposed on a semitransparent surface. Enzyme- and substrate-acting kinases are in green and blue, respectively. Bound AMP-PCP molecules are shown as sticks. Left and right, surface regions mediating asymmetric complex formation are highlighted in magenta (enzyme) and yellow (substrate), respectively. b, Close-up view of contacts at the enzyme’s catalytic site. c, Expanded views of the dimer interface distal to the active site showing multiple hydrogen bonding interactions.